Investors Can Calm Western Wildfires

in California. (Credit: J. Cook Fisher)

As severe wildfires leave their charred mark on the western United States this season, Conservation Finance Network interviewed Blue Forest Conservation (BFC) staff about the Forest Resilience Bond (FRB) project. This massive collaboration is bringing private finance to bear on ecological restoration to reduce the risk of these catastrophes.

Zach Knight and Leigh Madeira, cofounders of BFC, have pulled together a network of NGOs, researchers, lawyers, agencies and funders to support a massive ecological restoration effort that will weaken the harsh effects of fires in California and Colorado. It may expand to other states later. Investor, public and philanthropic capital will support creating safer ecosystems and hiring rural residents and Native Americans.

The FRB team released a report on Sept. 18 featuring the infographic below. It shows some of the many benefits investing in forest-fire prevention can bring to communities in the West.

According to Knight, the positive results don’t just relate to calming the severity of wildfires. They also include water quality, reduced sedimentation, flood control, and carbon retention. On the western slope of the Sierras, there is also an opportunity to increase water volume.

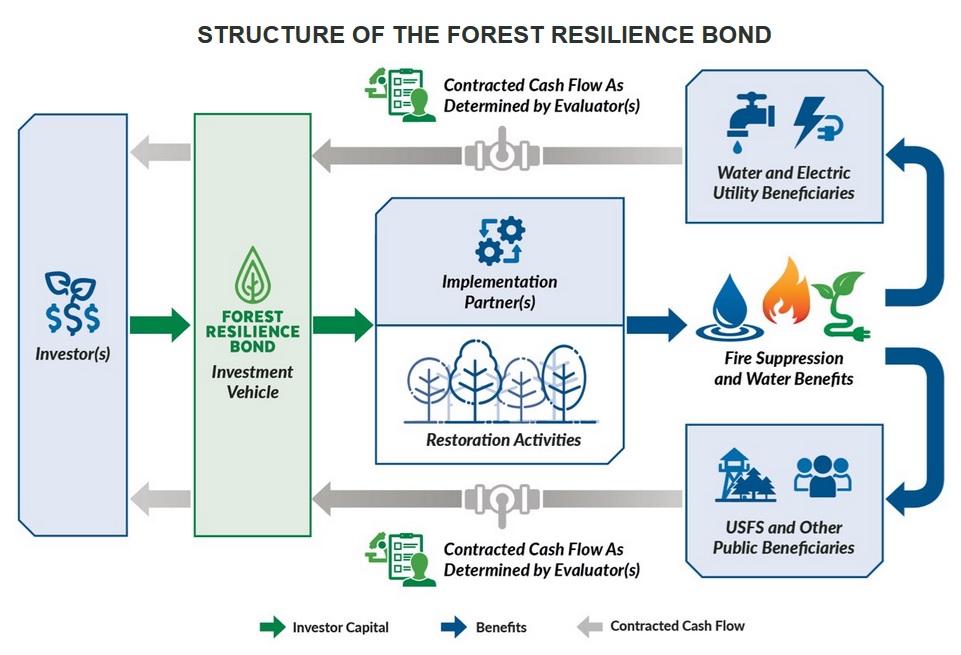

How will this flow of capital operate? The diagram below shows the mechanics of this multi-stakeholder process. BFC has been doing extensive groundwork to prepare its partnerships so that the bond financing will operate smoothly, deploying private capital to fund restoration with the appropriate safeguards in place.

CFN: Let’s talk about BFC’s report in an overall sense. What have you been working on?

Madeira: We have been working on the FRB for about 2.5 years now. We started this back when we were getting our MBAs at the Haas School of Business at Berkeley. It was a school project.

We competed with it at the Morgan Stanley Sustainable Investing Challenge and were fortunate enough to win that competition in 2015.

CFN: What are the specific components of what you’re doing and what are the technology aspects of them?

Knight: I’ll give you a high-level example of what the treatments would be. Forest restoration is something the Forest Service does on an everyday basis.

There is both a tremendous need and a tremendous backlog for this work. The efforts of the Forest Resilience Bond are really focused on trying to accelerate the scale and pace of ecological restoration, specifically in California but also in Colorado. This can expand across the western United States.

The treatments for the restoration differ from project to project.

One example would be fuels-reduction treatment – going into the forest and thinning out the small-diameter trees and brush. Sometimes it’s planting new species. Some of the national forests in California have places where conifers have come in and taken over where aspen had been before. The treatments would call for removing some of the conifers and planting aspens.

Most treatments will also include prescribed fire. The Forest Service will go in and reintroduce fire to try to regenerate the natural fire regime.

There’s also work around road decommissioning. There can be huge impacts to sedimentation and water quality from some of the dirt roads that run through our national forests. So after the work is done, decommissioning those roads and making sure they are in good shape is crucial.

That’s a good mix of what some of those treatments are. That’s all to restore the forest to a more natural density.

[We hope that] as fire comes back into the forest, you won’t see catastrophic wildfire. You’ll see ground fires that rejuvenate the soil. They’ll clear out some of the biomass that’s grown back during the fire cycle that has been disrupted.

CFN: How did you get the idea for this bond initially?

Madeira: We both have finance backgrounds. This is a bit different from us from sitting on Wall Street where we were 10 years ago.

There are four of us on this team. Our one partner and cofounder, Nick Wobbrock, is a former water resources engineer. He brought to our attention the facts that forest restoration affects water quality and water quantity and… is mostly being funded by the Forest Service. Even though it’s not funded nearly as much as it should be.

Zach said that given there isn’t as much work being done as there needs to be and there’s all these other groups that are involved, this could be an ideal situation for financing.

Zach and I had learned a lot about social-impact bonds and were really interested in that type of model. It creates all this value for a lot of different beneficiaries. It really seemed to check all the boxes. So if we could get everyone together, then this could be a really attractive investment opportunity.

CFN: What goals have you accomplished to date? How has your progress been so far?

Knight: When you look at a project like this, you’ve got to do two things and you’ve got to do them well. And they take quite a bit of time.

The first is developing the concept through a detailed process of stakeholder engagement to really understand what this needs to look like down the road.

When we started this, Leigh and I thought we’d be buried in spreadsheets, but the bulk of the work was engaging stakeholders. Helping bring people on board with the vision for this. Making sure everyone is looking ahead and looking in the same direction. I think the most important part of that is going and meeting with these stakeholders and listening.

The second thing is that you also need to be willing to be flexible. This is a project where we’ve had to pivot a number of times based on everything from federal contracting rules to just getting a better understanding of some of the operational challenges.

We thought initially this was entirely a finance problem. There’s other elements as well that without incorporating them into the mechanism, you can throw as much money as you want at this problem and it’s not going to fix it.

Trying to look at this a bit more holistically and being an incredibly good listening partner for the stakeholders we work with has been crucial in moving this forward.

In terms of deliverables, the first that comes to mind is this report. The second is siting of a few pilot projects. We’re working toward launching those pilot projects in 2018.

CFN: To what extent will this be happening on privately owned land versus government-owned land?

Knight: Our initial pilot projects are working on National Forest System land. We’ve been working with the Forest Service as a partner for about 2.5 years. We were, along with our partners at the American Forest Foundation and World Resources Institute, awarded a Conservation Innovation Grant from Natural Resources Conservation Service to bring this mechanism to work on both private land and cross-boundary work. The focus of that work is on Colorado right now.

CFN: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Knight: Because we are bringing private investment dollars in to fund this land management work, we need to be very careful that private investors are not dictating where this investment happens, what treatment is prescribed, or what contractors are hired.

We’ve been really thoughtful in our governance structure to try to address that.

We’re looking to the Forest Service and other partners to determine the location. The Forest Service will be [using] technical guides on how to do restoration. Investors are not involved in that process.

We see this within the conservation finance space as one of the first real opportunities to scale and use private dollars to support the sustainable management of public land. And we think that is pretty compelling proposition for both investors and natural resource managers.

One of the things the Forest Service focuses on is the need to hire local workers. Working with established forest collaboratives is crucial to ensuring local workers are hired for this restoration work.

Some forest collaboratives in California include native tribes. They’ll be engaged in the discussions and the decision-making. Where possible, the restoration work will include traditional environmental knowledge from the native tribes that are local.

A lot of the communities disproportionately impacted by fire are economically disadvantaged as well. Any efforts that can create rural jobs related to resilience is a really important part of these efforts as well.

Note: Natural Resources Conservation Service and the United States Forest Service are two funders of Conservation Finance Network.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.