Bridge Financing

This explainer is available in PDF format for non-commercial Creative Commons uses if it is shared with attribution and without remixing. We welcome your feedback. We encourage you to contact us if you decide to share it with a group.

A property with critical wetland habitat is on the market. The seller likes the idea of permanently protecting the wetland. The local land trust hopes to buy it, but doesn’t have the cash on hand to cover the entire asking price. The project would score well for a state grant and there’s a strong likelihood of it receiving funding – but public funding would not come through fast enough to meet the seller’s timeline.

This situation presents a perfect opportunity for the land trust to consider borrowing funds to cover the cost of acquisition. Loans can be used to bridge the financing gap between a conservation organization’s cash and the cost of an important acquisition or project.

Those considering conservation loans should carefully evaluate their preparedness and be open to the possibility that this may not be a viable strategy for their organization. Any organization must get its financial and management systems in order before lenders will provide a loan.

Sophisticated nonprofit organizations should think like for-profit businesses when considering this strategy. They should include lenders in early conversations about potential acquisitions or other projects and budget to incorporate the full administrative costs of projects.

When ready to borrow money, the organization’s staff and board should understand the nuances of using commercial bank loans or working with more mission-aligned lenders. A loan for conservation can have implications for future projects, helping to build community relationships and even jump-start fundraising.

Implementing Standard Financial Systems

Before borrowing money, a conservation organization needs to get its financial house in order. Any organization planning to borrow money for a land acquisition should be in compliance with the Land Trust Alliance (LTA) Standards and Practices. These guidelines broadly cover financial and ethical considerations for the responsible operation of a land trust.

A helpful Requirements Manual is published by the Land Trust Accreditation Commission, which was founded by LTA and operates independently. It provides detail on indicators from the standards and practices that demonstrate an organization’s eligibility to become accredited by the commission.

These guidelines include common nonprofit-management best practices. Both commercial and nonprofit lenders will expect conservation organizations to meet these standards:

- Organization keeps accurate records in a system compliant with Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP).

- Board of directors provides financial oversight and ensures that duties are separated appropriately for the scale of the organization.

- Written internal controls and accounting practices are in place to prevent misuse of funds.

- All unrestricted, temporally restricted, and permanently restricted funds are systematically tracked.

- Organization prepares a budget annually and evaluates progress against that budget.

- Budgeted and actual finances demonstrate income exceeding expenses—and any deficits should not be long-term trends. Organizations in deficit should have strategies in place to address their income shortfalls.

Conservation organizations can learn about gaps in their systems by asking a bank’s loan officer, “What would my organization need to do to qualify for a loan or line of credit?” While going through this checklist to prepare for borrowing money, a conservation group should also start an open dialogue with a local bank.

Preparing the Board of Directors to Oversee a Loan

Small organizations often underestimate the importance of educating board members before beginning the process of borrowing money. Boards may be reluctant to take on a loan to bridge the gap between a grant or pledged donation and a project’s full cost despite the low risk. Even if board members have personally used home loans to acquire their homes, use credit cards, or finance the purchase of cars, the jump to borrowing money for organizations where they volunteer can feel daunting.

Training can help board members to better understand their organization’s financing options and the benefits and risks associated with each option. Conservation organizations rarely have bank loan officers or finance experts on their boards to provide in-house expertise, so outside training is important.

The Land Trust Alliance offers educational sessions on borrowing money for land conservation at the annual LTA Rally and in regional conferences. Local training may be available through state land-trust service centers and regional land-trust associations.

The practice of raising and managing capital to support land, water, and natural resource conservation.

Network hosts an annual week-long Boot Camp that provides insight into innovative conservation and resource management. Nearby organizations are likely to know of other local and regional resources.Once an organization formally begins the loan process, that bank or nonprofit lender becomes another important resource for the board. If a conservation group begins working with a mission-aligned lender like The Conservation Fund, loan officers are available to participate in board meetings to answer questions or explain the loan process. This allows the lender to look at the inner workings of an organization while providing financial education and further support for the board and staff.

Securing a Loan

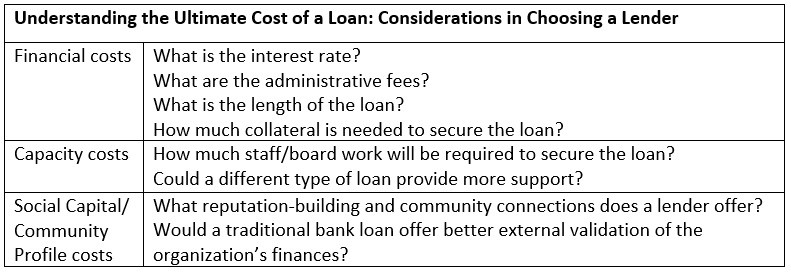

After a conservation organization has instituted rigorous financial systems and educated board members, it is ready to evaluate the nuances of borrowing money. Conservation organizations will find tradeoffs between traditional bank or credit-union loans and the lower-rate loans offered by mission-aligned nonprofits and foundations.

Mission-Aligned Lenders

Conservation lenders generally offer below-market-rate loans to nonprofits. Generally, these mission-aligned lenders do not qualify for market-rate loans from conventional banks. Land trusts and other nonprofits are uniquely qualified for these favorable conservation loans.

Federal law stipulates that nonprofits cannot generally offer below-market-rate loans to private, for-profit entities, even for projects that align with the organizations' missions. A below-market-rate loan to a private entity may violate the nonprofit’s public-service mission by providing the benefit of a discounted loan to a private individual. This could result in the organization losing its tax-exempt status.

The Conservation Fund manages a $50 million revolving loan fund, making it the largest conservation lender in the United States. The fund offers loans ranging from $12,000 to $10 million, averaging about $545,000, with terms of three months to three years.

The Norcross Wildlife Foundation lends up to $250,000 (average loan size is $160,000) for a one-year period to support land acquisition. The Open Space Institute offers grants and loans in priority areas of the eastern United States and Canada. The Resources Legacy Fund manages loan and grant programs for conservation efforts in California and across the West.

Additional resources may be available at the regional or community level. For example, some local community foundations offer program-related investments and other mission-aligned loans, which are explained below. Nearby land trusts may know of local funding opportunities.

Beyond the lower interest rates, conservation lenders offer a few advantages over traditional lenders. They can often process loans more quickly, which can be helpful in keeping up with a fast-paced transaction.

Low-interest-rate loans may also offer more flexibility in loan-security requirements. Collateral for a loan might include real estate being purchased or other assets held by the organization, as would be the case for a traditional commercial loan. In addition, collateral could also include operating reserve funds or even the personal assets of one of the borrower’s board members or a major donor.

Conservation lenders can also offer more support for borrowers. Repayment schedules may be flexible, and mission-driven lenders are more likely to adjust the repayment terms if a borrower needs more time or a repayment strategy doesn’t proceed as planned. Some conservation-loan programs also offer technical support on project and transaction financing.

Mission-aligned lenders can be particularly helpful in capitalizing on the momentum of a transaction. Conservation groups need nuanced fundraising and marketing strategies to capitalize on the momentum of a project. After a land trust uses a loan to buy threatened habitat, for example, fundraising may feel less urgent to the local community - but the loan still needs to be paid back. Conservation lenders typically have tips on how to message and explain this challenging situation.

Traditional Commercial Lenders

Conservation lenders aren’t a good fit for all borrowers. There are nuanced differences between traditional and mission-aligned lenders that go beyond the rates they charge. Banks have greater access to capital, can often move faster, and can offer longer terms like a traditional 30-year mortgage.

Traditional commercial lenders help a conservation organization make inroads in the local community. Working through a loan with a local bank is a great way to build relationships with valuable future board member candidates. Bank loan officers and branch presidents can bring strong local connections that contribute social capital to a conservation organization.

Another important consideration is the signaling opportunity. Qualifying for a traditional loan provides widely understood external validation of a conservation group’s management and financial capabilities. It signals that an organization must be sophisticated, fiscally sound, and financially savvy.

Although mission-aligned lenders like The Conservation Fund have rigorous standards for prospective borrowers, a traditional lender’s stamp of approval may be more impressive to an organization’s community.

Defining Types of Loans

Bridge Loans

Conservation organizations often use bridge loans to complete projects. These typically provide a few months to a few years of short-term financing, giving groups the cash on hand to complete projects that otherwise would have been out of reach.

The Conservation Fund’s bridge loans, for example, most often cover land acquisition, capital projects, or habitat restoration and provide financing while organizations await government grants (reimbursement or otherwise) or fundraising outcomes.

Lines of Credit

More sophisticated organizations may qualify for a line of credit. A line of credit is a financial arrangement between a lender and a customer that allows the borrower to draw funds up to a predetermined maximum balance.

Through a line of credit, a borrower can access funding at any time as long as the total outstanding debt does not exceed the maximum balance. The size of the line of credit may be based on the borrower’s contract and grant revenue or other assets. Funding can be revolving, which allows the borrower to repay and re-borrow funds, or non-revolving, in which the borrower cannot re-borrow the amount they have repaid.

A conservation organization that obtains a line of credit should expect to pay interest on any borrowed money. Many lenders also charge a non-use fee, typically 0.5 percent of undrawn funds, as compensation for keeping that balance available for use. Lenders often attach other stipulations for borrowers, such as making timely minimum payments on the credit-line balance.

A conservation group may face unevenly matched revenues and expenses over the course of a year. For example, the land trust might need to purchase a parcel before all funding is secured. Or a conservation group might find that the timing of its revenues and expenses don’t line up. Expenses might be spaced throughout the year, but donations are concentrated with year-end giving in December.

A line of credit can bridge that timing gap while speeding up the loan process and reducing the organization’s overhead costs.

Generally, a line of credit should support temporary capital needs. It will need to be repaid with a form of payment that may include a grant or contract. A line of credit should not support an organization that has been running an operating deficit.

Program-Related Investments

Through program-related investments (PRIs), foundations provide loans to mission-aligned projects.

A

Program-Related Investment

will have a lower interest rate or financial return objective than prevailing market rates for loans or investments of similar risk, duration, and credit quality.Foundations that make PRIs can tolerate more risk than commercial investors, so foundations may be able to fund organizations when the private sector cannot. PRIs can include familiar private-sector financing vehicles like loans, loan guarantees, and equity investments. Generally, PRIs supplement a foundation’s existing grantmaking work and serve projects for which grants would not be appropriate.

For example, a project might generate income. Under the terms of the

Program-Related Investment

, that cash flow would be set aside to pay back loans and equity investments. If the was a loan guarantee or credit enhancement, that cash flow would be set aside to cover obligations that the had secured.Although PRIs have generated great enthusiasm in philanthropic circles, research by Foundation Center suggests that this financing tool has limited reach. Generally, foundations will offer PRIs only to prior grantees. A conservation organization should not expect to secure a

Program-Related Investment

unless it has an existing relationship with a -granting foundation.Of the thousands of American grantmaking foundations, only a few hundred offer PRIs. The Norcross Wildlife Foundation and Resources Legacy Fund grant loans using PRIs, for example. But PRIs have yet to significantly expand the pool of capital available to support land conservation.

Learning from Case Studies

- In California, The Conservation Fund extended a loan to Big Sur Land Trust to refinance its historic headquarters building. The savings allowed the land trust to expand programming for underserved youth.

- In New York, the Finger Lakes Land Trust used a program-related investment from the Park Foundation to support a pivotal land-acquisition project.

- In Pennsylvania, the Countrywide Conservancy used a loan from the Norcross Wildlife Foundation to complete a time-sensitive land acquisition for a state park while the eventual owners, the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, completed their internal funding process.

- In Wisconsin, The Conservation Fund provided a bridge loan to help the River Revitalization Foundation purchase key parcels on the Milwaukee riverfront for a new arboretum.

Note: Our expert coauthors volunteer their time to assist our writers with these pieces.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or email the author via our contact form.